“But if, violently or otherwise, the populace deposes a just king, or if, as more frequently happens, it tastes the blood of the aristocracy and subjects the entire state to its wild caprice (and make no mistake about it, no tempest or conflagration, however great, is harder to quell than a mob carried away by the novelty of power), then the result is what Plato* so brilliantly described, if I can express it in Latin. (It’s not easy, but I’ll try.) ‘When’, he says, ‘the insatiable throat of the mob is parched with thirst for freedom, and when, thanks to the wicked servants it employs, it thirstily quaffs a freedom which instead of being sensibly diluted is all too potent, then, unless its magistrates and leaders are extremely soft and indulgent, and administer that freedom generously in its favour, it denounces them, arraigns them, and condemns them, calling them despots, kings, and tyrants.’”

Cicero, Republic and The Laws

Three years ago today, I was sitting in my office in Yerevan and reading Serzh Sargsyan’s resignation letter aloud to my staff. There was already much tension because there were rumors of what was coming. When I reached the part about him addressing the people for the last time, the tension was mounting. When I read «Ես թողնում եմ երկրի ղեկավարի, Հայաստանի վարչապետի պաշտոնը», the tension broke, pure elation poured forth. I carried on reading the rest of the text, but nobody was listening; I wasn’t even listening to myself.

The revelers in the street were already audible: the honking horns and excited curses directed at Sargsyan could be heard everywhere. I remember getting up and going to get a cup of water. My throat was dry.

Amid her euphoria, one of my staff members turned to me in bewilderment and said, “you look unhappy…why?” She couldn’t know my stomach was turning.

I had spent months researching a story I was going to write on the malaise that haunted Armenians. The perpetual sense of dissatisfaction with our country, people, and leaders. I wondered where it came from and why it seemed like a cloak fastened to our backs, inextricable from our essence. It was not after weeks of failing to prove my hypothesis that the malaise was founded upon ideology that I had realized that the real reason was the unceasing flood of vile lies about our heroes, government officials, the Church, elections, and the state of affairs in Armenia that were responsible. And the immoral cur I had discovered to have been the chief purveyor of these since the first years of Armenia’s independence was none other than the professionally crafted, camo-clad fraud to whom thousands of Armenians were now clamoring to entrust the future of the country.

“You look unhappy…why?” I inhaled. I took a moment to look at her before I responded. I couldn’t see myself but I knew I looked like I was at a funeral. Wasn’t I? Maybe not. It was too soon for the funeral: the throat had only just been cut.

I took a moment to compose myself, suppressing the wretched thoughts I was having from watching Armenia bleed to death from its self-inflicted wound. I pointed to Baghramyan Avenue outside and said to her with a trembling voice, “this is how our people send off a national hero, with rapturous profanity. What is there to be happy about?”

She looked at me with pity, as though I wasn’t yet aware that I had won the lottery; I looked at her, vainly hoping that I was wrong, that her cheerfulness from that day would remain forever.

Everyone went home early that day – but nobody went home.

Outside on the street, people came up to congratulate me. I didn’t react. They moved on. I walked down to the Presidential Palace where beaming youth were taking selfies with the police officers who were guarding the street during weeks of protests, the same police officers they had cursed for years.

I thought about going to Republic Square where the party was to continue. I thought it might help convince me that I was missing something. This many people couldn’t be wrong…right? But my legs were as immovable as the stone wall in front of the Presidential Palace. My dread was suffocating. I turned and went home.

It was the first time in weeks I didn’t open my laptop to see what was happening. It was done. That night, I sat with my wife and my friends Mher and Alen in the most somber living room in Yerevan. There were no smiles or toasts, just stillness laced with subdued fury and despair.

I can’t remember how that day ended.

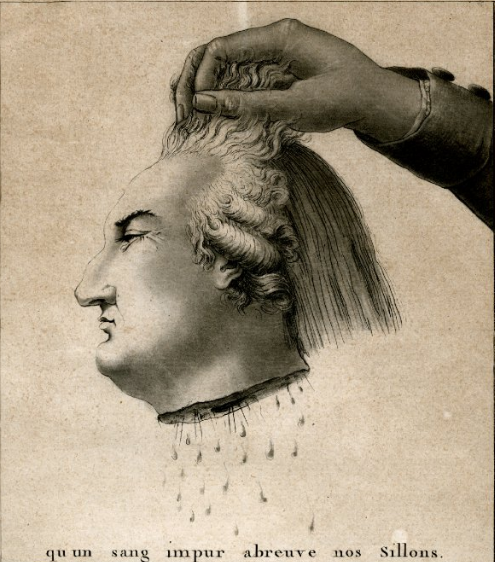

Three years ago, the Armenian Nation chose to become a part of the ignominious history of the mob, the mob that crucified Jesus, the mob that guillotined thousands in revolutionary France, the mob that raped and pillaged in Sumgait, the mob that filled the streets of Yerevan and Glendale in April of 2018. The ferocious, unthinking mass of bodies chanted and yelled, chanted and yelled, chanted and yelled, and finally got what they wanted: the figurative head of Serzh Sargsyan – and the ascent to power of their savior. The violence, death, and horror that accompanies the mob were delayed, but these came in due time; where the mob is, these lurk not far behind.

In three years, we lost not just lives and land, but hope, sweat, and love. Will we regain these things? Some, like the lives of our precious young men, no; some others, perhaps. But is there any reason to think we should? Are our people willing to reject the cowardice, pride, and avarice that led to April 23, 2018? Are our people ready to accept responsibility for our deepest failings? Are our people prepared for humility? If we are, let us start by asking the forgiveness of our children, and of our children not yet born, for leaving them with the burden of building the country we have always wanted but to accomplish which we have always preferred wizardry to work when it came time to do.

All those reading this who are able to vote in Armenia’s upcoming historic elections, or know people who are, please understand that former president Robert Kocharyan is Armenia’s last hope. Please vote or encourage people to vote for Kocharyan as the nation’s future is at stake.

Robert Kocharyan is Armenia’s only hope – Summer, 2021

https://theriseofrussia.blogspot.com/2021/06/president-robert-kocharyan-is-armenias.html

[…] BY: WILLIAM BAIRAMIAN The Armenite […]