Armenia is known for being in a rough neighborhood. What is less known is how Armenia became the most stable country in the region. The Armenite looks at Armenia and its neighborhood to see how the country came to be the most stable and what it means for Armenia’s future.

In 2005, the United States opened what was at the time the largest American embassy in the world on the shores of Lake Yerevan. It was befuddling to many – why build a huge embassy in a country where the US has few economic interests and fewer military interests? Especially since Armenia was surrounded by three countries – Georgia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – that had made their preference for American friendship clear.

Conspiracy theories abound: the USA was planning on going into Iran after it was done with Iraq so it wanted to have a base close by. And the Marines stationed at the embassy were proof – though Marines are stationed at every American embassy in the world – that Iran was indeed next.

Or, perhaps it was because the US expected there to be a political revolution like there was in neighboring Georgia so they preemptively built a large embassy to have a foothold in the country before the Russians or anyone else joined the party.

The real reasons were probably much simpler. The United States may have known years ago what is now clear: Armenia is the most stable country in the region.

***

“Those who are opposed to Great Leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s understanding ‘How happy is the one who says I am a Turk’ are enemies of the Republic of Turkey and will remain so. The Turkish Armed Forces maintain their sound determination to carry out their duties stemming from laws to protect the unchangeable characteristics of the Republic of Turkey. Their loyalty to this determination is absolute.”

Forgotten like most of Turkey’s tiffs with banana republicanism, in 2007 the country experienced what came to be known as the “E-Coup” or, euphemistically, “E-Memorandum,” in which the Turkish military blatantly displayed its opposition to the potential election to the presidency of Islamist candidate from the AK Party, Abdullah Gul. The head of Turkey’s army at the time, General Yasar Buyukanit, even seemed to relish his role as the architect of the memorandum, publicly stating that he himself wrote it.

From 1923 to 2007, Turkey experienced six coups – roughly one every 14 years – hardly making it a marker of a stable polity. In the first four iterations – 1960, 1971, 1980, 1993 – political violence swept the country. Although the United States and Europe usually preferred remembering their Cold War ally’s superficial lip service to democracy to the regular violation of its principles, Europe’s tepidity toward Turkish accession to the European Union may have been a projection of an underlying worry – or perhaps knowledge – that Turkey was not the stable beacon of democracy that it purported to be.

It wasn’t until the powerful Islamist government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan took on the military apparatus that the latter’s power and influence through the Ergenekon network was exposed. It seemed more and more the case that governments in Turkey were elected by the people but were approved by powers that be lurking in the dark, unseen but in control.

A parallel system of behind-the-scenes control that is likewise premised upon the pretense of democracy is how Iranian governance has worked since the 1979 revolution. But, instead of military puppet masters, it is the clerical apparatus that calls the shots in that country, through the all-powerful ayatollah.

Diverse and large, Iran’s autocratic government manages to keep order in a way Turkey hasn’t been able to with its Kurds. However, Iran’s foreign policy, plainly antagonistic toward the West – it seemed that the last president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, would take every opportunity to poke his finger in their eye – makes it a target in more ways than one.

Economically, it has been subject to tight sanctions by Western countries, severely limiting its ability to access large foreign markets for its products, particularly oil and gas. Militarily, it has taken on the role of Israel’s main enemy, regularly thumping its chest, probably to reassure Tehran-funded Hezbollah and its supporters in the Arab world that it is ever behind them.

The new president, Hassan Rouhani, seems to be a more willing partner than Ahmadinejad and he has expressed openness to reconsidering old positions – but it will not be easy. The three decades of enmity with the United States will take more than a fortnight to overcome and the niceties must eventually be complemented by substance. Until then, the ability of Iran’s current government to continue financing its existence will remain tenuous, as will its stability, amid economic pressures from the West and regional pressures from competitors Turkey and Saudi Arabia .

***

Failed States and Indexes

[pullquote]At the other end is, coming in the 178th place is Finland, land of Nokia and Teemu Selanne…[/pullquote]

Numbers are big business. Data is used for everything from making multi-billion dollar financial investments to advertising campaigns that predict if you are pregnant. The rush to quantify everything has not escaped international relations analysis and almost every major think tank and publication has attempted to claim a part of the market.

The Heritage Foundation ranks countries on their economic freedom. Transparency International has its Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). Reporters Without Borders measures press freedom in countries around the world. This does not even include the massive statistics operations of supranational organizations like the United Nations, World Bank, or the European Union.

So it should not be a surprise that there is also a Failed State Index. It is the brainchild of The Fund for Peace and the results are published every year in Foreign Policy magazine. States are ranked according to a dizzying number of parameters measured by a complex program called the Conflict Assessment System Tool (CAST).

The banality of such rankings is that they always have some Scandinavian country at the top of the list – bottom, in this case – and any number of African masochist-playgrounds-cum-countries that round out the other end. Putting that aside here, the numbers tell the story.

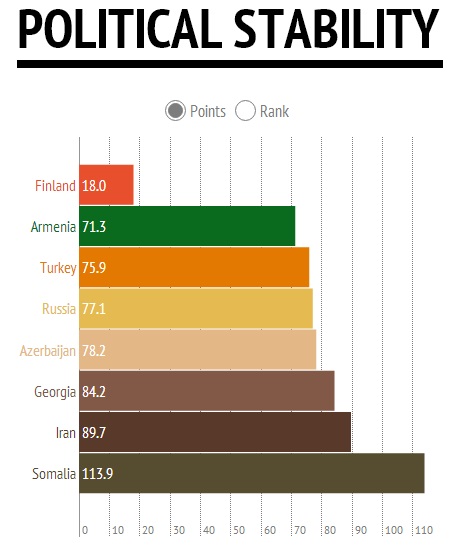

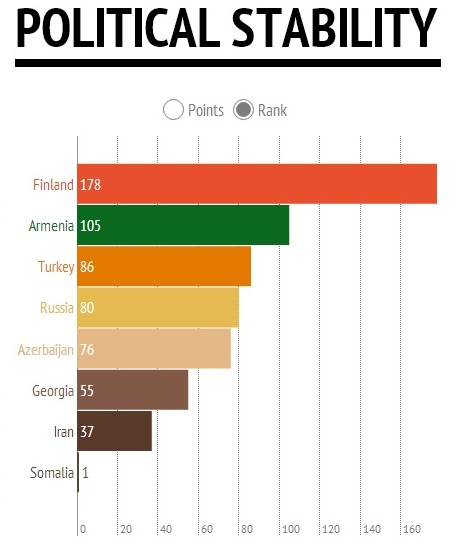

Somalia was the most failed state in 2013, coming in at number 1. It has had no functioning government in recent memory and is widely thought to be an apocalyptic mess mostly controlled by warlords. At the other end, coming in the 178th, place is Finland, land of Nokia and Teemu Selanne (it’s the best we could do).

In order from worst to best, Armenia’s neighbors are ranked: Iran (37th), Georgia (55th), Azerbaijan (76th), Russian (80th), Turkey (86th). Armenia is 105th.

For some of the reasons outlined above and many of them outlined below, these rankings seem to portray with a good deal of accuracy the reality of stability in these countries.

***

Internal Conflict

“Life and death seemed to have been left to the whims of the seating arrangement. In the densely packed crowd, those nearest the bombs absorbed much of the shrapnel and force, and were killed. Those away from them, and near the now vanished windows, had a chance.” New York Times. Beslan, North Ossetia, Russia.

Chechnya. Ingushetia. Dagestan. Faraway places that always seem to be in the news for the wrong reasons.

In 2002, terrorists from Chechnya took over a theater in Moscow and over 150 people were killed in the disarray of the rescue operation. Two years later, over 300 people were killed in a hostage crisis in Beslan, North Ossetia, where Chechen and Ingush terrorists took a school hostage and, again in the course of a rescue operation, plans on both sides went awry.

Although Russia has tried to quell terrorist activity, often through sheer brute force, attacks have continued: the latest were two explosions in the city of Volgograd in December 2013. Shortly before the start of the 2014 Sochi Olympics, which were taking place not far from Chechnya, a terrorist group released a video threatening attacks during the Games which, fortunately, did not materialize.

The reality is that much has not changed in the internal dynamics of Russia to expect that there will be a big change in how separatist groups operate or in what their demands might be. As events in the past few months proved, there remain destabilizing forces within Russia that are willing to use terrorism for their ends.

Adjoining part of Russia’s problem areas is its southern neighbor, Azerbaijan, which is on Armenia’s eastern border. Azerbaijan may not seem as volatile currently – it is not as big nor diverse as Russia – but its oiled, glossy exterior belies grave realities.

The powder keg of Azerbaijan, where the ruling Aliyev family has amassed billions of dollars in petro-wealth while most of the country’s residents suffer bubbled just slightly over in the regional town of Quba. In 2012, protesters gathered there and demanded the ouster of the governor whom they accused of dishonoring them. Subsequently, several of the protesters were imprisoned and sentenced to jail.

There are also, like in Russia, minorities with dreams of independence in Azerbaijan. The Talysh and Lezgin minorities have intermittently pursued greater autonomy with little success but there are groups within the country that continue to hold out hope for an eventual state or greater autonomy within Azerbaijan.

But the greatest wildcard are the hundreds of thousands of refugees displaced during the Artsakh War that have been kept living in squalid conditions. The Aliyev regime has chosen to keep these families in poverty as a sign that it does not accept the loss of Artsakh. It is also understood that president-dictator Ilham Aliyev seems to think by keeping people in these conditions, he will be able to perpetuate hatred of Armenians for being the cause of their suffering.

It is yet to be seen if the calculus of Aliyev & Co. will be to its benefit or detriment.

***

The Special Case of Georgia

Georgia as it appears on most maps is a shell of reality.

No less than two regions of Georgia – Abkhazia and South Ossetia – operate outside of the control of the central government. The Adjarian Autonomous Republic also, until recently, operated essentially as an independent state. Tblisi, the seat of government, has tried to assert control over its various territories in different ways, including force, intimidation, and questionable policies.

With a poor track record under the Soviet apparatchik Eduard Shevardnadze, the Rose Revolution brought hope that corruption, the strong-arm tactics of the government, and the chauvinism of Georgian authorities toward minorities in the country was going to be alleviated. The revolution’s leader, Mikheil Saakashvili, Western-educated and backed, promised reforms and a new way of doing things.

Not four years after being in office, demonstrators flooded the streets again, this time demanding that Saakashvili step down from the presidency.

In response, water cannons were sent in, tear gas was used against demonstrators, and mass arrests took place. In a starkly undemocratic move, the Imedi TV station was ransacked and closed down by government thugs. The UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, Louise Arbor, reprimanded Saakashvili and his government for the “disproportionate use of force.”

And this was only in Tblisi.

Ethnic strife inside Georgia came to a head in August 2008 when the Georgian military started shelling South Ossetia, already a de facto independent state. Aware that Russian intervention was likely, Saakashvili chose to hope for Western support. Russian support for South Ossetia came but Western support for Georgia didn’t. In a few days, the fate of South Ossetia was cemented to Russia’s and Georgia had lost another piece of territory.

Interestingly, the brazen antagonism that reinforced the separation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Georgia wasn’t enough reason to change course elsewhere in the country.

In the region of Samastkhe-Javakheti (Javakhk in Armenian), the largely Armenian population continued to be subject to intimidation by the authorities and remained the poorest region of the country.

Armenian churches and monuments throughout the country continued to be usurped by the Georgian Orthodox Church and Georgian authorities. In one particularly deplorable, if hardly publicized, case indicative of the abandon with which Armenians are subject to the whims of a variety of Georgian authorities, whether governmental or otherwise, Georgian priests of a formerly Armenian church in Kakhetia used Armenian tombstones as the foundation for their residential trailers.

As yet, however, the Armenian population, cognizant of the sensitive geopolitical situation their brethren to the south are in, have been less vocal – although not silent – than other minorities in Georgia about the continuous violation of their human rights.

***

Not Perfect

Armenia has had its set of growing pains.

With the fall of the Soviet Union came the excitement about self-rule but that was tempered when the scheming of Lenin and Stalin was realized when it was no longer of any use to their holds on power.

When Levon Ter-Petrosyan, the country’s first president, won reelection in 1996, the results were challenged by Vazgen Manukyan, his opponent. The latter alleged vote rigging and corruption and led thousands of protesters into the streets but by calling in the police and military, Ter-Petrosyan was able to disperse the crowds and the protests abated.

Soon thereafter, in 1998, Ter-Petrosyan fell out of favor with Prime Minister Robert Kocharyan and Defense Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and resigned from the presidency, ceding the position to Kocharyan. The departure was acrimonious but the transfer of power was peaceful and uneventful.

One year later, in a gruesome assassination, Sargsyan and seven other officials were gunned down during a session of parliament by crazed attackers who turned themselves in and were sentenced to life imprisonment. The unexpected and bold attack in the middle of the day, with popular war hero and now Prime Minister Sargsyan as the main target, marked a new low point in Armenian politics.

For almost ten years, there was little erratic political activity in Armenia, primarily ascribed to Kocharyan’s austere, no-nonsense leadership.

In 2008, Ter-Petrosyan reentered the political stage and attempted to stage a comeback. After losing the presidential elections to Serge Sargsyan (no relation to Vazgen Sargsyan), he refused to accept the results and called on the people to protest. Thousands heeded his call and not only came out to rallies, they began camping out in the areas surrounding the Opera in center of Yerevan.

Kocharyan, the outgoing president, called in law enforcement and military units to pacify what was increasingly becoming a tense atmosphere.

On March 1, under the cover of darkness, amid looting and clashes with police and military, ten people were killed in Freedom Square. The tragic deaths shocked the whole country and Kocharyan declared a state of emergency; Ter-Petrosyan called off further protests.

There has not been a definitive conclusion as to what took place on March 1 and who the responsible parties were. The deaths are commemorated annually.

Despite these graphic episodes, Armenia has been able to maintain a semblance of order. The main factor may be a considerable improvement in freedoms from the Ter-Petrosyan and Kocharyan administrations. Although problems still exist, hindrances to freedom of expression have largely been curtailed and indicators seem to suggest a trajectory of continued betterment.

Otherwise, unlike Turkey, Armenia’s military plays little to no direct role in politics. Vazgen Sargsyan, when he was defense minister, stated in a January 1998 interview that, “Armenia’s Armed Forces were created to fight against external enemies; Armenia’s Armed Forces are not going to get involved in political issues.” It’s a maxim that seems to have been carried forward in the years after his death.

Quite different from all of its neighbors, Armenia is largely homogeneous and has essentially no sectarian conflict as a matter of ethnic or religious differences. Another distinction in this regard is the good relations Armenia does have with the few small minorities that there are, among them Yezidis, Assyrians, and Molokhan Russians.

To summarize: tear gas and water cannons aren’t mainstays at protests, there isn’t a secessionist movement in the country, and people can, more or less, say whatever they want.

***

Armenia is stable. What of it?

The question, of course, is so what if Armenia is stable? Besides being a country that’s a good place for superpowers to build embassies, how is its stability important?

Harvard Law professor Mark J. Roe and Harvard Business School professor Joseph Siegel argued in a paper published in the Journal of Comparative Economics that political instability has a causal relationship with financial development. Coming to a similar conclusion was a report by International Monetary Fund economist Ari Aisen and colleague Francisco Jose Veiga that established that political instability can be detrimental to continue economic growth.

One reason that instability makes it difficult for the economy to grow is that policymaking suffers. If the government is unsure of itself and its future in making policies, it will determine how far ahead officials are thinking when planning for policies whose effects might not be discernible for many years to come. Or, by evaluating the past, we can see that instability in a country can unravel policies that had helped the country move forward on a path toward economic growth and development.

That’s internally.

Capital flows rarely being bound by national borders, investments from abroad can make a huge impact on a country’s economic and financial well-being. However, since international companies take significant pains to assess the risk in a country before entering its market, the level of stability is a matter of paramount importance. So it seems appropriate that many private assessors of political risk throughout the world are insurance companies like Aon or companies like Maplecroft.

Because political instability affects economic and financial growth does not mean that political stability will automatically translate into either type of growth. Rather, it is to underscore that without the impediment of political instability, growth is for the taking.

Stability is seldom indefinite. The world moves quickly and areas of stability one day could become war zones the next. So the lesson seems to be that building economic strength in those times of stability is the best preparatory and defensive measure in ensuring the inevitable difficult times are more bearable than they would be otherwise.

The importance of the exceptional level of stability in Armenia today is that there is the chance to solidify and strengthen the country in a way that hasn’t been possible in any living person’s memory. It is now easier to attract investment, engender confidence in financial markets, and build at a faster pace.

If Armenians are able to seize the opportunity and capitalize on it, the result may not only be that foreign countries are building embassies in Armenia but that Armenia starts building embassies in foreign countries.

William Bairamian is the founder and publisher of The Armenite. You can reach him at editor-at-thearmenite-dot-com.

Note: After this piece was written, Russia took control of Crimea from Ukraine, Turkey banned Twitter, and Georgia summoned former president Mikheil Saakashvili for questioning in the poisoning death of a former prime minister, his pardoning of four convicted murderers, corruption allegations, and the closing of a television station.

Very interesting article 🙂

It’s true that if Armenia were to capitalize on its political stability, that economic growth could lead to greater partnerships around the region and globally, but the questions as to who profits from economic growth and how that growth develops into per capita income is not, and can not, be addressed. Why can’t this be addressed? Armenia’s foreign partnerships are yet to develop the small nation on a whole and increase the living standards of its people. Acknowledging recent independence (23 years), recovery from a debilitating war and internal economic strife as previous barriers, Armenia has done quite well for itself. But, let us compare Armenia with Israel, for instance. Israel is comparable in size (Armenia 29,743 km2, Israel20,770 ), has more than double the population of Armenia, surrounded by nations that are not the friendliest, and yet Israel enjoys a Purchase Power Parity (PPP) of $35,833 per year per capita, that is almost 600% more than Armenia’s PPP of $6,128 per year per capita. Why the difference? Beyond their population, port trade and wealthy Jewish diaspora, Israel shares common goals, beliefs and has fostered a close relationship with the United States and Western nations, despite the size of their embassy. In Armenia, there’s a need to foster better relationships with regards to Western nations that has not yet come to fruition. This is inclusive of it’s warmly relationship with Russia because without Russia, Armenia would not be where it is today. What remains is the need for developing farsighted relationships with global partners that have Armenia’s best interest in mind, not personal gain, which has been an issue in the past and now.

If Armenia is to play a global role, it needs to foster global relationships with economic growth as an aim. Armenia needs to encourage a better image by holding high standards to local and international law, foster governmental programs that work for the people in a real and palpable way, and in doing so reclaim an image of integrity, connecting Armenians worldwide with their nation There’s a need for embassies in other countries, both for Armenian populations in those countries and for Armenia’s future economic and foreign policies.

Case in point, Ethiopia. If Armenia can achieve observer status in the African Union, as its Anatolian neighbor, Turkey, has maintained since 2005, it would be a huge strategic achievement. Addis Ababa is the capital of the African Union, and a new expansive headquarter campus is being built with the foresight of greater economic and governmental cooperation in Africa with international partners. Multifarious development projects are continuing in Africa and will be continuing for the foreseeable future. If Armenia is transitioning toward becoming a knowledge exporter, owing to its lack of natural resources, then the best place to build relationships with countries who have a demand for development would be the seat of the African Union, in Addis Ababa. Not to mention the Armenian population that has existed there for over two centuries. If an Armenian embassy was established there (independent of the representational embassy that is in Cairo which is located in the tumult that is the Middle East and is growing increasingly unwelcoming for Christians to live) it would help to set a keystone in the arch that is Armenians’ long-standing good and favored relations with Ethiopia. Closer relationships with Western nations and African nations can help Armenia gain an influential position on the global playing field and reciprocally help its own holistic economic growth.

chaussure foot enfant

Hi there, just was aware of your weblog through Google, and found that it’s truly informative. I’m gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll be grateful in the event you proceed this in future. Many other people will probably be benefited from your writing…

[…] Parliament/ “The Centennial without this regime” is that the government must be removed and a “stable democracy” be put in place. The rest is murky. But, listening to their interviews and following their less […]

[…] into their psyche as permanently as their stone masonry around them. But their geo-political fate is confronted by a deeper question: What does a 21st century Armenia look like? What would it look […]