September 2 is Artsakh Independence Day. For the past thirty years, it represented the hope of a nation born anew, one whose refusal to be subjugated to the whims of murderous neighbors would carve an entirely different path than the melancholic past so familiar to every Armenian. Last year, this hope was crushed; the solution is not to pretend like nothing has changed.

It is important to remember Artsakh Independence Day, just as we remember the Battle of Avarayr or the heroic stand at Sardarabad. But it is important that we not pretend that Artsakh is anything but what it is today: a protectorate of a superpower whose interests, for the moment, align with those of Armenians who are concerned about keeping one of the last pieces of the historic Armenian homeland Armenian.

Artsakh Independence Day should be remembered as a means of inspiring reflection. That is, self-reflection, as a people. For twenty-nine years, Artsakh was the ultimate source of pride for Armenians, a pedestal upon which any Armenian could stand and announce to the world entire that Armenians were no longer the fearful and obedient sheep easily led to slaughter; that Armenians had finally understood that they lived among wolves; that Armenians learned from the wolves; that Armenians had become the wolves.

Despite the resounding aplomb with which one might speak about Artsakh, the collective Armenian psyche was able to comprehensively divorce the pride it felt in Artsakh’s existence as an independent state victorious over genocidal peoples from the very people who created this reality.

One by one, the men who sacrificed their safety, their families, and their friends, the ones who rejected dubious propositions of peace, the ones who held guns, commanded troops, and wrested the independence of a land under foreign rule for centuries, were rendered the villains of the entire play. The ones who built armies, who grit their teeth and stayed when hundreds of thousands left, and who continued the political fight were blamed for everything from petty swindlers looking for easy Diasporan prey to the brash and moronic behavior of every last hoodlum and self-styled boss in the country. Perhaps it was in recognition of their monumental achievements that “the people” expected these men to be omnipotent, snapping their fingers and solving all the problems of a destitute country reeling from the twin humanitarian disasters of a massive earthquake and bloody war poetically timed at the dawn of independence; or, perhaps it was the simplistic nature of our immature and malleable political minds unable to comprehend the complexities of building a functioning country in these circumstances.

And so it was.

Those who voluntarily left the country in the early 90s sought and found the perfect scapegoat in the heroes who stayed, fought and, yes, in many cases received the spoils of war in the subsequent years (or did they think they were going to be the feared or respected shot caller in Armenia from their perches in Moscow, Glendale, and Brighton Beach?). It was because of these men who were commanding and fighting in Stepanakert, Shushi, Martakert, and Fizuli that they decided to leave Yerevan.

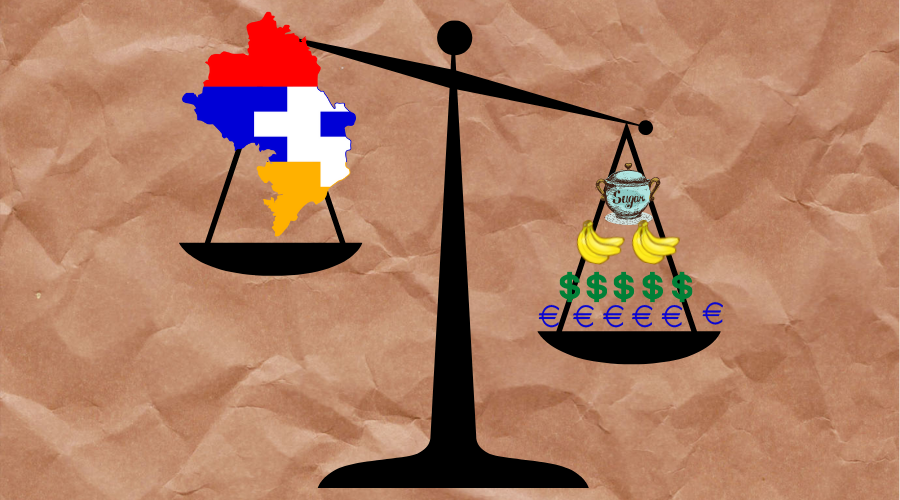

Those who stayed needed an explanation for why things didn’t improve at the pace at which they felt they deserved. After all, their father was a physicist and mother was a nurse and in the Soviet times they were respected and required the same deferential treatment from everyone including the boy next door who was now wealthier than they were because he opened a market on the corner (there were an oddly high number of these even though the industry was supposedly oligarch-ized). They, like everyone in Armenia, had settled upon importing bananas or sugar but everyone knew that that one guy controlled the importation of one and that other guy controlled importation of the other and therefore they could not involve themselves in either trade, thus leaving them with absolutely zero options of what to import from the whole wide world. It was bananas and sugar that every Armenian needed and every Armenian wanted to provide. What better scapegoat, then, than the gruff, inarticulate, and quiet Artsakhtsis and villagers who now controlled important posts in government?

And let us not forget the old Diasporans who reveled in the opportunity to become a part of the homeland, only to find a sweet-talking descendant of the salesman of the Brooklyn Bridge to hand a bag of cash to in order to buy a property or start a business only to see their money disappear and angrily march on over to one of the many Armenian newspapers at-the-ready to print whatever salacious details about the crime there were and for which those responsible were the heads of state and select government ministers. Everyone recognized that this, of course, would be a preposterous proposition in any other country: that the leaders of the country should be held responsible for every two-faced crook out to fleece any willing givers – but this was Armenia, our homeland and it was supposed to be perfect, absolutely perfect, like the paintings in everyone’s house. And if it wasn’t then, gosh darn it, every Armenian had the right – nay, the duty – to sound every last imperfection of the country from the rooftops of their homes across the world.

Working slowly and steadily to build a powerful country amid the perilous circumstances in which Armenia found itself be damned, there was no better time than right after independence for every last Armenian to air every last personal grievance about the country and whatever fellow Armenian they were cross with. NOW was the time for this. We hadn’t waited 1,000 years for statehood not to seize the opportunity to bludgeon our homeland and its countless imperfections. This was, after all, what all good liberal democracies did and because we wanted to be like France, the United States, and Liechtenstein, it was incumbent on all Armenians to pretend like we, also, had the size, wealth, and geographic blessings of former empires, current empires, and principalities in choosing how to behave as citizens and concerned Diasporan parties. In fact, if one needed money to help with opening an NGO or “media company” that would lend legitimacy to their bile factory, there was plenty to be had by anyone willing to sell any semblance of principle that may have yet resided in some atom of their being. “Ask what your country hasn’t done for you and what it needs to do in order for you to vest yourself in its future” was the motto of the day.

All of these patriotic Armenians thumped their chests with the utmost vigor at the mere mention of Artsakh, of course. It was the Armenian Nation that won the war in Artsakh; it was best to avoid specifics lest anyone get bogged down in the inconvenience of confronting the cognitive dissonance of hating the people who gifted you the thing you purportedly love. Loved to talk about, at least. When it came to doing, few were as inclined as when it was about talking. Even when others were doing, there was always a problem. Well-founded, surely, because all Armenians were undoubtedly destroying the reputation of the country and doing things like discouraging donations to the Armenia Fund, which was building several projects annually in Artsakh and other strategic regions purely out of patriotic duty. It was nothing personal. It was just that Armenia Fund was stealing all the money and building the roads, hospitals, schools, water and electricity systems, and community centers with…actually, nobody offered an explanation as to how they were able to do this because they just never bothered to visit these places or preferred, in their cognitively dissonant psychology, to ignore how they were able to drive from Goris to Stepanakert on the best-paved highway in Armenia. Or they were just deceptive scoundrels who purposely misinformed their compatriots because they were paid agents of foreign governments and foreign foundations and that was, literally, their job.

Whoever said patience is a virtue was obviously not an Armenian. How could it be that Armenia had not become the Switzerland of the Caucasus as every last delusional platitudinous ape mindlessly asked in the whole 5, 10, 20 years that it had had? How is it that Georgia was able to achieve such great success in such a short amount of time like losing vast swaths of its territory in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, turning its southwestern corner into a Turkish vilayet, and achieving about the same GDP per capita as Armenia even after all the European-oriented reforms? Could Armenia not emulate this country with access to the sea and Azeri-Turkish gas and oil transiting through it? Yes, Armenia went from malnutrition and people freezing in the winters to cheap and plentiful food, round-the-clock water and electricity, and skyrocketing industries like winemaking that in a few years were challenging robust competitors like the infallible Georgians but the importation of sugar and bananas remained under the control of that one guy and that other guy, respectively. And it just so happened that the guy who created the Armenian energy crisis and his cacophonous hillbilly sidekick-cum-yellow journalist agreed. No, the heroes of Artsakh needed to be removed because, liberating Artsakh aside, they were not allowing the Armenian people, who each felt a personal duty to import bananas and sugar, to import bananas and sugar.

So, yes, let us remember Artsakh Independence Day. Let us likewise remember that it was a relatively small collective of fearless men who gifted Artsakh to us. And let us recognize that by rejecting those men, by finding excuses to not build on what we had, and by allowing the personification of the Seven Deadly Sins to become prime minister of Armenia, we were the ones who lost it.

Ուրիշ տարբերակ չկա՝ ազատ Արցախը էլի պիտի տեսնենք:

Comments are closed.